Subtle Things: An Interview with Judy Fiskin

AT: I wanted to ask you first about your earlier work because that's how I discovered your art. Could you speak a little about what set you apart from the New Topographics photographers? 1

JF: Well, most of the people in the Topographics talk a lot about the political implications of land use. And I was interested in the decorative decisions. Like, what are they? Where did they come from?

I'm interested in quirky taste that is totally unconventional. I'm interested in the relationship between taste and class. One of my films, Fifty Ways to Set the Table, was a documentary on the table setting competition at the LA County Fair. And they were judging on etiquette and creativity, and—without saying so—taste. There's a set of conventional rules that you follow, for dressing, for setting the table, for decorating your house. For the upper classes, it's like class maintenance. And then for the classes below it's, not always, but often aspirational.

AT: Vernacular aesthetics in architecture and art are usually perceived to occupy the bottom of the hierarchy of class and taste. And the impression your photos and videos had on me was this sense of freedom from judgment.

JF: Yeah, for me, it represents freedom. And also, it's its own kind of creativity, not that there isn't taste. Having taught art for so many years, sometimes I feel like what we're teaching graduate students is taste. And so what I say to them is watch out, we're teaching you taste, you might want to reject it.

AT: Would you ever describe your own work as subtle? What do you think in general about subtlety?

JF: It's always interested me that when people write about my work, they've almost never mentioned the humorous aspect—maybe because that's somewhat subtle. Maybe a little less subtle in the films. The photographs have this kind of standoffish quality, but they are also funny. Some of them. Humor is not prized in the art world, as much of it is deadly serious. One of the great revelations as I got older after seeing survey shows of conceptual art was that so much of it is funny or mischievous. I saw this piece by Michael Asher—a blank wall. You go, and you look at the label, and it tells you that if you stand in front of that wall, you're going to feel some air being blown at you from above. And it happened, and it completely delighted me.

I don't know if I think my art is subtle or not. It's hard to say, but the one aspect of it that I think comes off as subtle is the humor. What do you think?

AT: I would say so, yes. I lean towards things that people describe as subtle in both art and architecture, and writing. When the presence of style or artistic hand is not so heavy, it feels like there's more space to be aware of the subject and take it in. I tend to be more attracted to things that are open-ended in that sense. And I think that by being a little bit less personal on the surface, it feels more personal in the end.

JF: Yeah, I understand what you're saying.

One thing about subtlety is that it surprises you when you get it.

AT: Focusing on vernacular subjects, or things viewed as ordinary, often makes for ticklish situations where you're more prone to discovering something because the most ordinary things are typically the oddest.

JF: Yes. I made this film Confessions of An iPhone Addict about using my iPhone as a camera for the first time, and in the beginning, I just stayed in my neighborhood. I take this walk less now, but I used to take this walk every day, just up and down. The streets in my area are abnormally long. So I would go three blocks and come back and what I liked about it is that there was always something to notice about the landscaping changing just with the season. Just within a week, suddenly, something's in bloom, but you have to seek it out. So I had a little sequence about looking at the leaves on the trees or the ground. I went out after a storm one day, and I noticed the leaves on the ground always sitting on wet spots. And I've never seen that before. I think that that's what always happens. So I had arranged it into categories. First, I had leaves, and then I had leaves after a rainstorm, and there it was, and I'm not even sure people would get what the difference was. They weren't puddles, but they were still wet right around them when everything around was dry. There were still these little wet spots with the leaves in the middle of them.

So yeah, I'm interested in subtlety. Just staying in my neighborhood, there's so much to notice, but they're subtle things.

AT: Do you think your work has elements of nostalgia or bleakness in it?

JF: Certainly not nostalgia. Bleakness—yes, some of the early work was trying towards certain signs of the LA atmosphere and emotional bleakness. These little houses all alone. I didn't show them in their place in the neighborhood. I dodged the site so they would be a kind of ghostly impression because I was thinking of the houses as singular objects. One of the effects of that was a kind of solitary feeling. And a kind of bleakness.

AT: It feels like interiors and exteriors always play an active narrative role in your work. In I'll Remember Mama, I thought the description of her balcony was so wonderfully poetic. Do you think about architecture often?

JF: Well, I'm always noticing it where I go—sometimes great architecture, but mostly the vernacular. So that's the kind like a form of thinking.

What I felt about vernacular architecture in terms of non-photographic ideas was that in those days, in the 70s, we didn't realize how prosperous the country was. We lived near Sunset and Fairfax, in a California bungalow that might have been a kit house—often on one part-time salary and renting this great house with built-ins.

AT: Yeah, the housing was affordable.

JF: Those little houses now go for more than a million dollars. But at the time, it made me feel like this was really just a kind of democratic housing. Because the houses were fantastic, they had wood floors, big kitchens, French doors, and good airflow. So I felt like they were kind of luxuries that lots of people could afford. I did have that thought.

AT: Do you have any favorite buildings in LA?

JF: I drive around sometimes as if I'm photographing, so I really like neighborhoods. What used to be inexpensive neighborhoods aren't anymore. What I would do now if I were going back to photographing, I wouldn't get that far from home, but I would be looking for neighborhoods that I've never been in or streets in neighborhoods that I've never been on.

Even in my own neighborhood, there are streets that I've never been on. That, to me, is just like heaven.

For people from outside LA, it's always about the hills and the ocean, but the heart of LA is still all these houses. Have you ever read Los Angeles, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies by Reyner Banham?

AT: Yes, I love that book.

JF: You know, I was reading that right at the beginning. He's one of the first architectural writers who ever talked about what he called The Plains of Id.. All these houses are really important in LA. Architecture writers don't get that. It was the first book that I ever found that talked about that, from the 70s. And I felt very proprietary about having discovered this. And so my first reaction was, he doesn't even live here; he shouldn't be talking about this. And then I realized, no, this is a great thing that he got that.

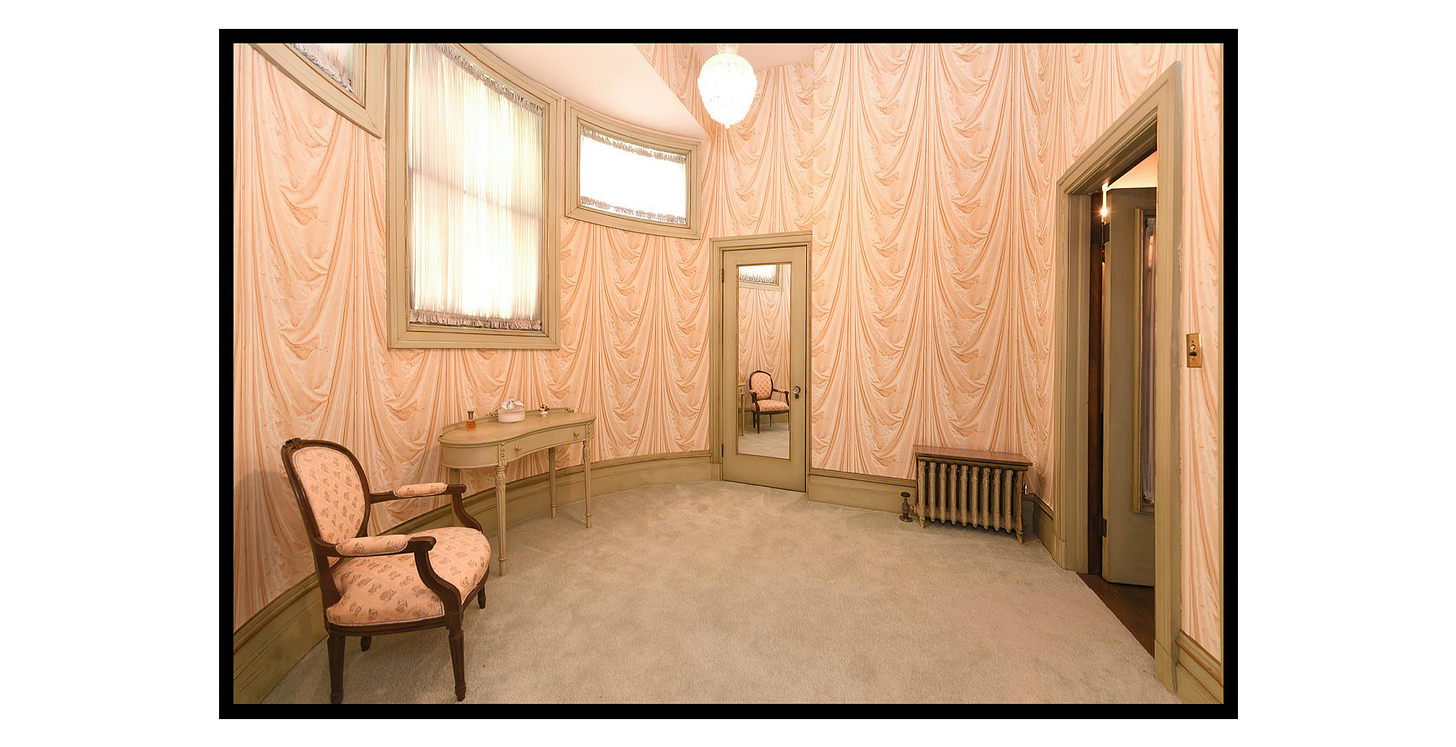

AT: Your latest series of photographs, The Way We Live Now, are altered real estate images of expensive properties across the country. Real estate photos already have this natural oddness, where something feels off about the furniture or the scale. Did you alter the images to make them appear even stranger?

JF: Yeah, I wanted to make them odder. But in a way, that has to do with the bleakness that we talked about. I wanted to make them look uncanny.

Friends of ours sold their house about ten years ago, which was the first time I became aware of the idea of staging. They took a long time to sell it. In the meantime, they had been told to get rid of most of their furniture. So they were living in this semi-unfurnished house. That alone is one of the principles of real estate selling—not make the house look empty, but make it look bigger. And one way to make it look bigger is to take a lot of the furniture out. Then the realtors would put around their own little ornaments, right? So one of the main things we did was take those off of tables when we could. We would take out the light fixtures, the can lights but still left most elements in.

I wanted to make things look arranged but empty.

New Orleans is a great place to look at those photographs. Because in New Orleans, they're into saturated bright colors, mixed whichever which way. So they're not wasteful, but they're wild and exuberant.

AT: May I ask if you have any favorite artists at the moment?

JF: Who would I leave the house for?

David Kordansky has a really good sculpture program. So I like a lot of stuff I see there. I really like Katharina Fritsch, Fiona Connor. I think Kathleen Ryan's work is really witty.

I will leave the house for sculpture before anything. I'm less interested in photography than you might think I should be.